“It’s not a matter of taste; insects will be a food choice for everyone when there’s a cultural model for them and they’ve gone through the generational shift.”

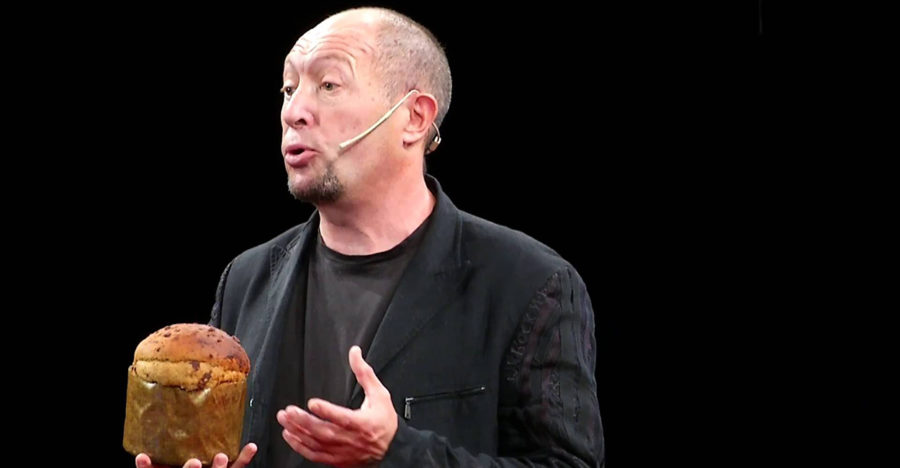

Marco Ceriani of Italbugs

“Excuse me waiter, there’s a bug on my plate. Can you bring me a new one?”

“But madame, that’s your dinner!”

It sounds like a cartoon from the kind of magazine you’d read at the beach, but it’s something that could actually happen – insects are the food of the future. This is more than just the latest trend, it’s a culinary tradition already practiced by roughly 2 billion people in 90 countries around the world. But what’s to like about them? Those who have tasted them say they’re delicious. They’re kind of like prawns and taste faintly of vanilla. The majority of Italians would turn their nose up at the idea of putting a cricket or grub in their mouth, but in actuality we wouldn’t even notice we’re eating insects. They’re mainly used in powder form, or as ingredients in other, more complex foods. We went to interview an Italian pioneer in this sector, Marco Ceriani, founder and CEO of Italbugs, who talked to us about the potential of this food trend.

When we talk about new food trends, insects are becoming more and more of a main player. But in Italy, they’re still a shock. How did you choose to dedicate yourself to edible insects?

The idea began in Bangkok in 2006, while I was working in sports nutrition. I met athletes from northern Thailand and I saw them taking bags from the fridge that were full of some sort of food that I didn’t recognize. It would be put into soup or fried, and then eaten. When I asked what it was, they told me that it was insects and my first reaction was “that’s disgusting!” But I was curious, and so I decided to team up with a university in Bangkok to work with edible insects in their entomology and agronomy faculty.

You knew right away that Italians weren’t ready to hear about insects on their plates, so you wrote a book to help them see that it wasn’t that strange. Is that right?

Yes, I wrote a book called Si fa presto a dire insetto (Insects: More than meets the eye) where I explain that Leonardo da Vinci talked about them, and that even the ancient Romans ate them. So really, it’s an innovation with solid roots in the past. Then I decided to turn the idea into a real project during the 2015 Expo, also because it was the perfect stage where all the world was watching. Working with the Belgian embassy and setting myself up with the staff in the Lodi PTP Science Park to do research, I was able to produce Panseta, the world’s first panettone made with silkworm flour.

Silkworms are a surprise – we’d have thought you’d use other types of insects. Which ones are best suited for human consumption?

Silkworms were one of the edible insects introduced in Belgium back in 2011. Some of the advantages are that they’re environmentally friendly and completely non-toxic. I should actually mention that FAO (the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization) recognizes 1900 types of insects, but in Belgium there are less than 10. They must have nutritional value, and they can’t be parasites or contain dangerous substances. Grasshoppers were recently excluded, and ants are definitely not suitable because they contain formic acid. On the other hand, crickets get the stamp of approval, as do grubs and silkworms. Simply put, every country will use the insects it has, even if they don’t all currently allow the production or sale of them.

Like Italy, right?

Yes, exactly. We have accepted the fact that you cannot produce anything made from arthropods there, so we came to the Netherlands to get certification to produce and sell products made with edible insects. We specifically chose the University of Wageningen because it’s the top university in the world for publishing research on food and agriculture. In addition, the Netherlands have always used insects for aquaculture, whereas the rest of Europe is just getting to that point now. Belgium and Holland are the trailblazers, but legislation that will even out the whole sector is coming in the next few months. Italy is behind however, because insects are seen only as a parasites in food. The movement is going to be quashed by the law and we’ll only be able to import them from abroad.

So where are we from a legal standpoint in Europe?

There’s a 3-phase plan: in July 2017, insects will be introduced for aquaculture; in October/November 2017, for poultry feed; in January 2018 as a Novel Food – that is, under the regulations for new foods. But keep in mind that this doesn’t mean insects will be in their original form for human consumption. They’ll usually be made into flour and supplements.

Now that we’re up to speed with entomophagy (a diet that includes insects), we’re ready to move to the kinds of products you decided to launch with Italbugs. What can you tell us?

Noi abbiamo due tipi di prodotti: il primo si chiama clean protein, e sono pillole create dalle tarme della farina, ovvero un alimento in polvere con il 75% di proteine che si può mettere nei cibi o ingerire in pastiglie. L’altro è il Panseta, il primo panettone realizzato con farina di bachi da seta, che sarà commercializzato a breve. Il baco da seta crea una farina bianca e una palatabilità che è molto simile alla vaniglia, quindi è l’insetto ideale per questo dolce, in più conserva il gusto italiano perché le materie prime sono Made in Italy

Are there advantages compared to traditional flour?

Yes, and they’re significant. The main benefit is that it contains very few carbs and is high in protein. For example, silkworms are between 60 and 80% protein. And the yield is extremely high. Just think that one hectare of land used to grow soybeans can produce a ton of protein per year, while the same land used for insects, which also consume less water and emit almost no carbon dioxide, can reach near 150 tons. The environmental impact is estimated to be 10 times less than for livestock, thanks to the fact that insects don’t product methane, can be fed with scraps, and have a short life cycle.

And are there disadvantages?

From what we know right now, entomophagy has just one risk, which is that it could trigger shellfish intolerances. But that has been observed with the whole insect and doesn’t happen when using just a flour or fat derived from the insect.

So there are plenty of benefits, and very few drawbacks. Is the lack of insects in our diets just a cultural issue?

Most definitely. At the moment that’s our biggest hurdle to clear. Newer generations don’t pose the same problems with culinary traditions because they’re open to new foods from around the world. For example, my daughter will say “dad, tonight are we having pizza, sushi or kebabs?”, but talking to a 70-year-old, I would never propose sushi or kebabs. It’s not a matter of taste; insects will be a food choice for everyone when there’s a cultural model for them and they’ve gone through the generational shift. In fact, it won’t be scientists who legitimize insects as food – it’ll be chefs.

It’s a really interesting project, but how will you develop it in the future?

Among our many ideas for the future, we definitely don’t want to stop with panettone. We’d like to make a whole range of baked goods using silkworms. At the moment we’re blocked by legislation, and we’re waiting to see where and how we can sell them, because that’s where food innovation starts.